Predicting Election Results from Football Statistics (1936–2020): An Archival Analysis in a Real-World Example

Kenneth M. Cramer, Rebecca Pschibul, and Alexander J. Cramer

Scientists are in the business of predicting events (like failed picnics from rain showers) based on empirically salient factors or antecedents (like barometric pressure and wind speed). This business rests on the assumption of determinism—that our universe is knowable with properties that can be measured and understood in a sound theoretical framework.

In the early days of a research program, investigators hope to identify significant correlations to the phenomenon of interest to home in on those antecedents, which should later prove to be empirically salient. This data-driven model relies on patterns within the data to direct theoretical development, but is not without its pitfalls.

We hope to show how the analysis and marriage of two seemingly unconnected events can lead to specious conclusions. Specifically, we will illustrate how the outcome of a National Football League game can reliably predict the winner of a US national presidential election. This should help educators for both high school and college/university outline the difference between correlation and causation, plus the dangers of data-driven mining exercises for theory building (cf. interpretation of linear models in the Common Core State Standards in Mathematics).

On occasion, sports statisticians identify unusual associations between sporting events and social phenomena. Decades ago, for example, Koppett’s Cycle suggested the decline or growth of the New York Stock Exchange for the year could reliably predict the winner of the NFL Super Bowl (specifically their conference alignment). That is, the Super Bowl winner would hail (at least originally) from the American conference if the market declined over the course of the year, but would hail from the national conference if the market increased.

Additionally, in The Impact of Professional Football Games Upon Violent Assaults on Women, G. F. White, J. Katz, and K. E. Scarborough uncovered violent crime statistics from Virginia that showed when the Washington Commanders won more NFL games throughout the season, the levels of violence against women increased—even when derived across various forms of violence. The authors believed more victories and fan support offered license to fans in the neighboring commonwealth to dominate women.

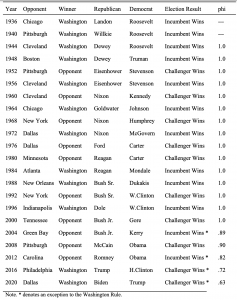

More recently, Fans, Football, and Federal Elections: A Real-World Example of Statistics, and ‘Redskins Rule’: MNF’s Hirdt on Intersection of Football & Politics reviewed the relationship between the winners of the United States presidential election in November and the most recent Washington Commanders’ home game (known as the “Washington Rule”). Since the inception of the franchise (originally the Boston Redskins in 1932), the incumbent party (Republican or Democrat) maintains control of the White House if Washington wins their most recent home game prior to the election, but a Washington loss implies a power transition by January 20. This pattern began in 1936 and continued unbroken (phi coefficient = 1.0) until the November 2004 election, when the victors from Green Bay would have predicted a presidential win for John Kerry (Democrat challenger).

For each year since 1936, Table 1 lists the Washington Commanders’ most recent home game opponent, plus the outcomes of both the game and presidential election (challenger vs. incumbent). Although the cycle was rejoined in 2008, it failed in 2012 (Carolina / incumbent-Obama), 2016 (Washington / challenger-Trump), and 2020 (Washington / challenger-Biden). Even with these four exceptions, the various association test statistics are significant: phi (20) = .633, p = .003; Pearson χ2 (1) = 8.82, p = .003, likelihood ratio (1) = 9.4950, p = .002; and the contingency coefficient = .535, p = .002. Indeed, the binomial distribution suggests that after only five successful game-election results, the pattern is reliable beyond chance expectations (p = .037). In sum, one would be compelled to conclude that the Washington game outcome (at home) constitutes a significant and reliable antecedent (predictor) of the federal election.

For both high-school and early college/university statistics and probability educators, this exercise should prove useful along many fronts. It begs the question that although two variables may move together perfectly (at least until 2004), may we conclude football directly affects elections, elections affect football, or a third unidentified variable affects them both? Indeed, what theoretical foundation might be drawn upon to explain such a connection? As Jules Henri Poincaré famously stated:

“Science is built up with facts as a house is with stones; but an accumulation of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones a house.”

This further illustrates the chief danger of data-driven models to build theories, since we can find ourselves going down conceptually unconnected alleys. With the availability of myriad databases and statistics, today’s computers can mine mountains of data quite effortlessly and reveal various as yet undiscovered associations. The solution to this trap is continued use of theory-driven science, in which defendable predictions can be made from a currently (even if imperfectly) developed theory of rational and testable hypotheses.

Furthermore, the philosophical underpinnings of determinism here warrant mention, since the identification of significant antecedents that may predict an election winner will surface (with considerable strength) following the results of this one key football game. Certainly more relevant factors (outside the NFL) can predict political outcomes, including gender-, age-, and education-stratified polling closer to the much anticipated Tuesday in November. So too, more relevant factors (outside of US politics) can explain the outcome of a football game, including recent trades, injuries, or shifts in coaching personnel. However, the connection of the two (football and elections) in a causal bridge remains tenuous.

To entertain another post-hoc (even convoluted) explanation, perhaps it is the case that the political leanings of fans at the Washington home game affect their general sentiment to their football club as played in the nation’s capital. That is, as it was argued in Fans, Football, and Federal Elections: A Real-World Example of Statistics, “the election to come may predict the game to be, so that a future event predicts one in the present.”

Before closing, we should note that 2020 was an exceptional year for a variety of reasons. To begin, the novel coronavirus pandemic affected virtually all world events, from sports attendance to mail-in ballot elections. Moreover, the NFL recognized the role it could play as a larger organization in addressing anti-black racism, allowing team players to kneel during the national anthem in support of those ongoing social and political struggles. In addition, that same spirit of equity, diversity, and inclusion permeated the demand for a franchise name change (currently the Washington Commanders), since Redskins was deemed derogatory. The Atlanta Braves baseball franchise faced similar pressure, as did the Cleveland Guardians (formerly Indians) and the Edmonton Elks (formerly Eskimos). Finally, the federal election results of that year were disputed by millions of Americans who believed the election had been rigged. These factors may aid educators in highlighting for students how the analysis of data in real-world contexts must acknowledge real-world events that may affect investigators’ interpretations.

Further Reading

Koppett, L. February 11, 1978. Carrying statistics to extremes. The Sporting News, 9.

Koppett, L. September 19, 1981. Statistics are best used with a grain of salt. The Sporting News, 9.

Koppett, L. November 11, 1984. The stock market theory on the ropes. Peninsula Times Tribune, A-2.

Koppett, L. January 4, 1985. The perfect stock theory collapses. Peninsula Times Tribune, A-2.

Ratcliffe, S. 2018. Oxford essential quotations (6th edition). Oxford University Press.